A review of the etymology of the term Mathematics (Μαθημα-τικα) from its origin derived from the Ancient Greece Etymological dictionary and period.

Reviewing some text and etymological interpretations found in reference publications, Wikipedia and other education content sources. All sources will be reference at the beginning of each definition.

Invitation to Greek Lanaguage academics and linguisits with a specialisation in Ancient Greek would allow verification and a formal standardised definition to be adopted in all mathematical curriculum and text.

The introduction in the education system of students understanding of the etymological interpretation of the subject terms – which forms the first part of knowledge to learn in a eduation and curriculum subject its related science.

It was with such an comprehensive discipline and approach, that allowed me to develop the standardised procedural Numerical and Mathematics program – “Developed and Advanced Theoretical Methods in Learning Numerical Systems and Mathematics”.

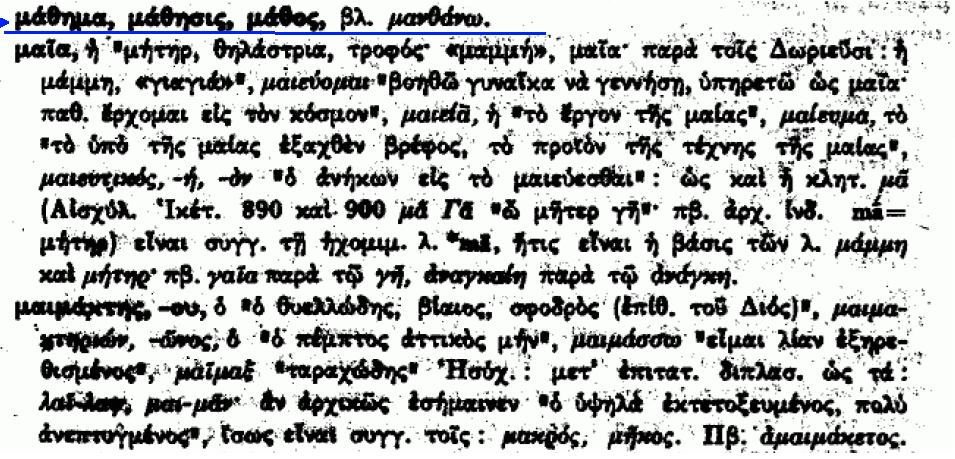

Wikipedia

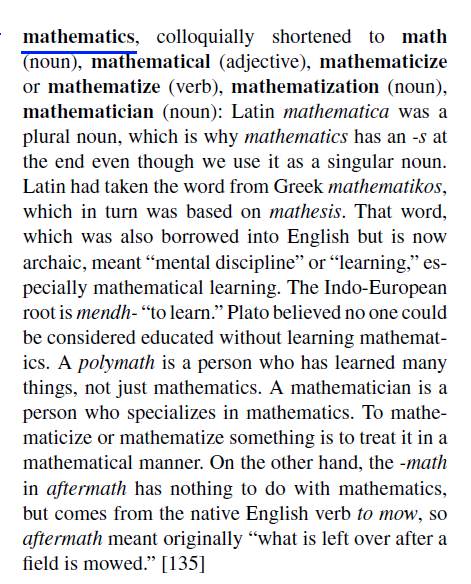

The word mathematics comes from Ancient Greek máthēma (μάθημα), meaning “that which is learnt”,[11] “what one gets to know”, hence also “study” and “science”. The word came to have the narrower and more technical meaning of “mathematical study” even in Classical times.[12] Its adjective is mathēmatikós (μαθηματικός), meaning “related to learning” or “studious”, which likewise further came to mean “mathematical”.[13] In particular, mathēmatikḗ tékhnē (μαθηματικὴ τέχνη; Latin: ars mathematica) meant “the mathematical art”.[11]

Similarly, one of the two main schools of thought in Pythagoreanism was known as the mathēmatikoi (μαθηματικοί)—which at the time meant “learners” rather than “mathematicians” in the modern sense. The Pythagoreans were likely the first to constrain the use of the word to just the study of arithmetic and geometry. By the time of Aristotle (384–322 BC) this meaning was fully established.[14]

In Latin, and in English until around 1700, the term mathematics more commonly meant “astrology” (or sometimes “astronomy“) rather than “mathematics”; the meaning gradually changed to its present one from about 1500 to 1800. This change has resulted in several mistranslations: For example, Saint Augustine‘s warning that Christians should beware of mathematici, meaning “astrologers”, is sometimes mistranslated as a condemnation of mathematicians.[15]

The apparent plural form in English goes back to the Latin neuter plural mathematica (Cicero), based on the Greek plural ta mathēmatiká (τὰ μαθηματικά) and means roughly “all things mathematical”, although it is plausible that English borrowed only the adjective mathematic(al) and formed the noun mathematics anew, after the pattern of physics and metaphysics, inherited from Greek.[16] In English, the noun mathematics takes a singular verb. It is often shortened to maths or, in North America, math.[17]

Before 1000 BC[edit]

- ca. 70,000 BC – South Africa, ochre rocks adorned with scratched geometric patterns (see Blombos Cave).[1]

- ca. 35,000 BC to 20,000 BC – Africa and France, earliest known prehistoric attempts to quantify time (see Lebombo bone).[2][3][4]

- c. 20,000 BC – Nile Valley, Ishango bone: possibly the earliest reference to prime numbers and Egyptian multiplication.

- c. 3400 BC – Mesopotamia, the Sumerians invent the first numeral system, and a system of weights and measures.

- c. 3100 BC – Egypt, earliest known decimal system allows indefinite counting by way of introducing new symbols.[5]

- c. 2800 BC – Indus Valley Civilisation on the Indian subcontinent, earliest use of decimal ratios in a uniform system of ancient weights and measures, the smallest unit of measurement used is 1.704 millimetres and the smallest unit of mass used is 28 grams.

- 2700 BC – Egypt, precision surveying.

- 2400 BC – Egypt, precise astronomical calendar, used even in the Middle Ages for its mathematical regularity.

- c. 2000 BC – Mesopotamia, the Babylonians use a base-60 positional numeral system, and compute the first known approximate value of π at 3.125.

- c. 2000 BC – Scotland, carved stone balls exhibit a variety of symmetries including all of the symmetries of Platonic solids, though it is not known if this was deliberate.

- 1800 BC – Egypt, Moscow Mathematical Papyrus, finding the volume of a frustum.

- c. 1800 BC – Berlin Papyrus 6619 (Egypt, 19th dynasty) contains a quadratic equation and its solution.[5]

- 1650 BC – Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, copy of a lost scroll from around 1850 BC, the scribe Ahmes presents one of the first known approximate values of π at 3.16, the first attempt at squaring the circle, earliest known use of a sort of cotangent, and knowledge of solving first order linear equations.

- The earliest recorded use of combinatorial techniques comes from problem 79 of the Rhind papyrus which dates to the 16th century BCE.[6]

Syncopated stage[edit]

1st millennium BC[edit]

- c. 1000 BC – Simple fractions used by the Egyptians. However, only unit fractions are used (i.e., those with 1 as the numerator) and interpolation tables are used to approximate the values of the other fractions.[7]

- first half of 1st millennium BC – Vedic India – Yajnavalkya, in his Shatapatha Brahmana, describes the motions of the Sun and the Moon, and advances a 95-year cycle to synchronize the motions of the Sun and the Moon.

- 800 BC – Baudhayana, author of the Baudhayana Shulba Sutra, a Vedic Sanskrit geometric text, contains quadratic equations, and calculates the square root of two correctly to five decimal places.

- c. 8th century BC – the Yajurveda, one of the four Hindu Vedas, contains the earliest concept of infinity, and states “if you remove a part from infinity or add a part to infinity, still what remains is infinity.”

- 1046 BC to 256 BC – China, Zhoubi Suanjing, arithmetic, geometric algorithms, and proofs.

- 624 BC – 546 BC – Greece, Thales of Miletus has various theorems attributed to him.

- c. 600 BC – Greece, the other Vedic “Sulba Sutras” (“rule of chords” in Sanskrit) use Pythagorean triples, contain of a number of geometrical proofs, and approximate π at 3.16.

- second half of 1st millennium BC – The Luoshu Square, the unique normal magic square of order three, was discovered in China.

- 530 BC – Greece, Pythagoras studies propositional geometry and vibrating lyre strings; his group also discovers the irrationality of the square root of two.

- c. 510 BC – Greece, Anaxagoras

- c. 500 BC – Indian grammarian Pānini writes the Astadhyayi, which contains the use of metarules, transformations and recursions, originally for the purpose of systematizing the grammar of Sanskrit.

- c. 500 BC – Greece, Oenopides of Chios

- 470 BC – 410 BC – Greece, Hippocrates of Chios utilizes lunes in an attempt to square the circle.

- 490 BC – 430 BC – Greece, Zeno of Elea Zeno’s paradoxes

- 5th century BC – India, Apastamba, author of the Apastamba Sulba Sutra, another Vedic Sanskrit geometric text, makes an attempt at squaring the circle and also calculates the square root of 2 correct to five decimal places.

- 5th c. BC – Greece, Theodorus of Cyrene

- 5th century – Greece, Antiphon the Sophist

- 460 BC – 370 BC – Greece, Democritus

- 460 BC – 399 BC – Greece, Hippias

- 5th century (late) – Greece, Bryson of Heraclea

- 428 BC – 347 BC – Greece, Archytas

- 423 BC – 347 BC – Greece, Plato

- 417 BC – 317 BC – Greece, Theaetetus

- c. 400 BC – India, write the Surya Prajinapti, a mathematical text classifying all numbers into three sets: enumerable, innumerable and infinite. It also recognises five different types of infinity: infinite in one and two directions, infinite in area, infinite everywhere, and infinite perpetually.

- 408 BC – 355 BC – Greece, Eudoxus of Cnidus

- 400 BC – 350 BC – Greece, Thymaridas

- 395 BC – 313 BC – Greece, Xenocrates

- 390 BC – 320 BC – Greece, Dinostratus

- 380–290 – Greece, Autolycus of Pitane

- 370 BC – Greece, Eudoxus states the method of exhaustion for area determination.

- 370 BC – 300 BC – Greece, Aristaeus the Elder

- 370 BC – 300 BC – Greece, Callippus

- 350 BC – Greece, Aristotle discusses logical reasoning in Organon.

- 4th century BC – Indian texts use the Sanskrit word “Shunya” to refer to the concept of “void” (zero).

- 4th century BC – China, Counting rods

- 330 BC – China, the earliest known work on Chinese geometry, the Mo Jing, is compiled.

- 310 BC – 230 BC – Greece, Aristarchus of Samos

- 390 BC – 310 BC – Greece, Heraclides Ponticus

- 380 BC – 320 BC – Greece, Menaechmus

- 300 BC – India, Bhagabati Sutra, which contains the earliest information on combinations.

- 300 BC – Greece, Euclid in his Elements studies geometry as an axiomatic system, proves the infinitude of prime numbers and presents the Euclidean algorithm; he states the law of reflection in Catoptrics, and he proves the fundamental theorem of arithmetic.

- c. 300 BC – India, Brahmi numerals (ancestor of the common modern base 10 numeral system)

- 370 BC – 300 BC – Greece, Eudemus of Rhodes works on histories of arithmetic, geometry and astronomy now lost.[8]

- 300 BC – Mesopotamia, the Babylonians invent the earliest calculator, the abacus.

- c. 300 BC – Indian mathematician Pingala writes the Chhandah-shastra, which contains the first Indian use of zero as a digit (indicated by a dot) and also presents a description of a binary numeral system, along with the first use of Fibonacci numbers and Pascal’s triangle.

- 280 BC – 210 BC – Greece, Nicomedes (mathematician)

- 280 BC – 220BC – Greece, Philo of Byzantium

- 280 BC – 220 BC – Greece, Conon of Samos

- 279 BC – 206 BC – Greece, Chrysippus

- c. 3rd century BC – India, Kātyāyana

- 250 BC – 190 BC – Greece, Dionysodorus

- 262 -198 BC – Greece, Apollonius of Perga

- 260 BC – Greece, Archimedes proved that the value of π lies between 3 + 1/7 (approx. 3.1429) and 3 + 10/71 (approx. 3.1408), that the area of a circle was equal to π multiplied by the square of the radius of the circle and that the area enclosed by a parabola and a straight line is 4/3 multiplied by the area of a triangle with equal base and height. He also gave a very accurate estimate of the value of the square root of 3.

- c. 250 BC – late Olmecs had already begun to use a true zero (a shell glyph) several centuries before Ptolemy in the New World. See 0 (number).

- 240 BC – Greece, Eratosthenes uses his sieve algorithm to quickly isolate prime numbers.

- 240 BC 190 BC– Greece, Diocles (mathematician)

- 225 BC – Greece, Apollonius of Perga writes On Conic Sections and names the ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola.

- 202 BC to 186 BC –China, Book on Numbers and Computation, a mathematical treatise, is written in Han dynasty.

- 200 BC – 140 BC – Greece, Zenodorus (mathematician)

- 150 BC – India, Jain mathematicians in India write the Sthananga Sutra, which contains work on the theory of numbers, arithmetical operations, geometry, operations with fractions, simple equations, cubic equations, quartic equations, and permutations and combinations.

- c. 150 BC – Greece, Perseus (geometer)

- 150 BC – China, A method of Gaussian elimination appears in the Chinese text The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art.

- 150 BC – China, Horner’s method appears in the Chinese text The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art.

- 150 BC – China, Negative numbers appear in the Chinese text The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art.

- 150 BC – 75 BC – Phoenician, Zeno of Sidon

- 190 BC – 120 BC – Greece, Hipparchus develops the bases of trigonometry.

- 190 BC – 120 BC – Greece, Hypsicles

- 160 BC – 100 BC – Greece, Theodosius of Bithynia

- 135 BC – 51 BC – Greece, Posidonius

- 78 BC – 37 BC – China, Jing Fang

- 50 BC – Indian numerals, a descendant of the Brahmi numerals (the first positional notation base-10 numeral system), begins development in India.

- mid 1st century Cleomedes (as late as 400 AD)

- final centuries BC – Indian astronomer Lagadha writes the Vedanga Jyotisha, a Vedic text on astronomy that describes rules for tracking the motions of the Sun and the Moon, and uses geometry and trigonometry for astronomy.

- 1st C. BC – Greece, Geminus

- 50 BC – 23 AD – China, Liu Xin

1st millennium AD[edit]

- 1st century – Greece, Heron of Alexandria, Hero, the earliest, fleeting reference to square roots of negative numbers.

- c 100 – Greece, Theon of Smyrna

- 60 – 120 – Greece, Nicomachus

- 70 – 140 – Greece, Menelaus of Alexandria Spherical trigonometry

- 78 – 139 – China, Zhang Heng

- c. 2nd century – Greece, Ptolemy of Alexandria wrote the Almagest.

- 132 – 192 – China, Cai Yong

- 240 – 300 – Greece, Sporus of Nicaea

- 250 – Greece, Diophantus uses symbols for unknown numbers in terms of syncopated algebra, and writes Arithmetica, one of the earliest treatises on algebra.

- 263 – China, Liu Hui computes π using Liu Hui’s π algorithm.

- 300 – the earliest known use of zero as a decimal digit is introduced by Indian mathematicians.

- 234 – 305 – Greece, Porphyry (philosopher)

- 300 – 360 – Greece, Serenus of Antinoöpolis

- 335 – 405– Greece, Theon of Alexandria

- c. 340 – Greece, Pappus of Alexandria states his hexagon theorem and his centroid theorem.

- 350 – 415 – Byzantine Empire, Hypatia

- c. 400 – India, the Bakhshali manuscript , which describes a theory of the infinite containing different levels of infinity, shows an understanding of indices, as well as logarithms to base 2, and computes square roots of numbers as large as a million correct to at least 11 decimal places.

- 300 to 500 – the Chinese remainder theorem is developed by Sun Tzu.

- 300 to 500 – China, a description of rod calculus is written by Sun Tzu.

- 412 – 485 – Greece, Proclus

- 420 – 480 – Greece, Domninus of Larissa

- b 440 – Greece, Marinus of Neapolis “I wish everything was mathematics.”

- 450 – China, Zu Chongzhi computes π to seven decimal places. This calculation remains the most accurate calculation for π for close to a thousand years.

- c. 474 – 558 – Greece, Anthemius of Tralles

- 500 – India, Aryabhata writes the Aryabhata-Siddhanta, which first introduces the trigonometric functions and methods of calculating their approximate numerical values. It defines the concepts of sine and cosine, and also contains the earliest tables of sine and cosine values (in 3.75-degree intervals from 0 to 90 degrees).

- 480 – 540 – Greece, Eutocius of Ascalon

- 490 – 560 – Greece, Simplicius of Cilicia

- 6th century – Aryabhata gives accurate calculations for astronomical constants, such as the solar eclipse and lunar eclipse, computes π to four decimal places, and obtains whole number solutions to linear equations by a method equivalent to the modern method.

- 505 – 587 – India, Varāhamihira

- 6th century – India, Yativṛṣabha

- 535 – 566 – China, Zhen Luan

- 550 – Hindu mathematicians give zero a numeral representation in the positional notation Indian numeral system.

- 600 – China, Liu Zhuo uses quadratic interpolation.

- 602 – 670 – China, Li Chunfeng

- 625 China, Wang Xiaotong writes the Jigu Suanjing, where cubic and quartic equations are solved.

- 7th century – India, Bhāskara I gives a rational approximation of the sine function.

- 7th century – India, Brahmagupta invents the method of solving indeterminate equations of the second degree and is the first to use algebra to solve astronomical problems. He also develops methods for calculations of the motions and places of various planets, their rising and setting, conjunctions, and the calculation of eclipses of the sun and the moon.

- 628 – Brahmagupta writes the Brahma-sphuta-siddhanta, where zero is clearly explained, and where the modern place-value Indian numeral system is fully developed. It also gives rules for manipulating both negative and positive numbers, methods for computing square roots, methods of solving linear and quadratic equations, and rules for summing series, Brahmagupta’s identity, and the Brahmagupta theorem.

- 721 – China, Zhang Sui (Yi Xing) computes the first tangent table.

- 8th century – India, Virasena gives explicit rules for the Fibonacci sequence, gives the derivation of the volume of a frustum using an infinite procedure, and also deals with the logarithm to base 2 and knows its laws.

- 8th century – India, Sridhara gives the rule for finding the volume of a sphere and also the formula for solving quadratic equations.

- 773 – Iraq, Kanka brings Brahmagupta’s Brahma-sphuta-siddhanta to Baghdad to explain the Indian system of arithmetic astronomy and the Indian numeral system.

- 773 – Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm al-Fazārī translates the Brahma-sphuta-siddhanta into Arabic upon the request of King Khalif Abbasid Al Mansoor.

- 9th century – India, Govindasvāmi discovers the Newton-Gauss interpolation formula, and gives the fractional parts of Aryabhata’s tabular sines.

- 810 – The House of Wisdom is built in Baghdad for the translation of Greek and Sanskrit mathematical works into Arabic.

- 820 – Al-Khwarizmi – Persian mathematician, father of algebra, writes the Al-Jabr, later transliterated as Algebra, which introduces systematic algebraic techniques for solving linear and quadratic equations. Translations of his book on arithmetic will introduce the Hindu–Arabic decimal number system to the Western world in the 12th century. The term algorithm is also named after him.

- 820 – Iran, Al-Mahani conceived the idea of reducing geometrical problems such as doubling the cube to problems in algebra.

- c. 850 – Iraq, al-Kindi pioneers cryptanalysis and frequency analysis in his book on cryptography.

- c. 850 – India, Mahāvīra writes the Gaṇitasārasan̄graha otherwise known as the Ganita Sara Samgraha which gives systematic rules for expressing a fraction as the sum of unit fractions.

- 895 – Syria, Thābit ibn Qurra: the only surviving fragment of his original work contains a chapter on the solution and properties of cubic equations. He also generalized the Pythagorean theorem, and discovered the theorem by which pairs of amicable numbers can be found, (i.e., two numbers such that each is the sum of the proper divisors of the other).

- c. 900 – Egypt, Abu Kamil had begun to understand what we would write in symbols as ��⋅��=��+�

- 940 – Iran, Abu al-Wafa’ al-Buzjani extracts roots using the Indian numeral system.

- 953 – The arithmetic of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system at first required the use of a dust board (a sort of handheld blackboard) because “the methods required moving the numbers around in the calculation and rubbing some out as the calculation proceeded.” Al-Uqlidisi modified these methods for pen and paper use. Eventually the advances enabled by the decimal system led to its standard use throughout the region and the world.

- 953 – Persia, Al-Karaji is the “first person to completely free algebra from geometrical operations and to replace them with the arithmetical type of operations which are at the core of algebra today. He was first to define the monomials �

, �2

, �3

, … and 1/�

, 1/�2

, 1/�3

, … and to give rules for products of any two of these. He started a school of algebra which flourished for several hundreds of years”. He also discovered the binomial theorem for integer exponents, which “was a major factor in the development of numerical analysis based on the decimal system”.

- 975 – Mesopotamia, al-Battani extended the Indian concepts of sine and cosine to other trigonometrical ratios, like tangent, secant and their inverse functions. Derived the formulae: sin�=tan�/1+tan2�

and cos�=1/1+tan2�

.

Symbolic stage[edit]

1000–1500[edit]

- c. 1000 – Abu Sahl al-Quhi (Kuhi) solves equations higher than the second degree.

- c. 1000 – Abu-Mahmud Khujandi first states a special case of Fermat’s Last Theorem.

- c. 1000 – Law of sines is discovered by Muslim mathematicians, but it is uncertain who discovers it first between Abu-Mahmud al-Khujandi, Abu Nasr Mansur, and Abu al-Wafa’ al-Buzjani.

- c. 1000 – Pope Sylvester II introduces the abacus using the Hindu–Arabic numeral system to Europe.

- 1000 – Al-Karaji writes a book containing the first known proofs by mathematical induction. He used it to prove the binomial theorem, Pascal’s triangle, and the sum of integral cubes.[9] He was “the first who introduced the theory of algebraic calculus“.[10]

- c. 1000 – Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi studied a slight variant of Thābit ibn Qurra‘s theorem on amicable numbers, and he also made improvements on the decimal system.

- 1020 – Abu al-Wafa’ al-Buzjani gave the formula: sin (α + β) = sin α cos β + sin β cos α. Also discussed the quadrature of the parabola and the volume of the paraboloid.

- 1021 – Ibn al-Haytham formulated and solved Alhazen’s problem geometrically.

- 1030 – Alī ibn Ahmad al-Nasawī writes a treatise on the decimal and sexagesimal number systems. His arithmetic explains the division of fractions and the extraction of square and cubic roots (square root of 57,342; cubic root of 3, 652, 296) in an almost modern manner.[11]

- 1070 – Omar Khayyam begins to write Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra and classifies cubic equations.

- c. 1100 – Omar Khayyám “gave a complete classification of cubic equations with geometric solutions found by means of intersecting conic sections“. He became the first to find general geometric solutions of cubic equations and laid the foundations for the development of analytic geometry and non-Euclidean geometry. He also extracted roots using the decimal system (Hindu–Arabic numeral system).

- 12th century – Indian numerals have been modified by Arab mathematicians to form the modern Arabic numeral system .

- 12th century – the Arabic numeral system reaches Europe through the Arabs.

- 12th century – Bhaskara Acharya writes the Lilavati, which covers the topics of definitions, arithmetical terms, interest computation, arithmetical and geometrical progressions, plane geometry, solid geometry, the shadow of the gnomon, methods to solve indeterminate equations, and combinations.

- 12th century – Bhāskara II (Bhaskara Acharya) writes the Bijaganita (Algebra), which is the first text to recognize that a positive number has two square roots. Furthermore, it also gives the Chakravala method which was the first generalized solution of so called Pell’s equation

- 12th century – Bhaskara Acharya develops preliminary concepts of differentiation , and also develops Rolle’s theorem, Pell’s equation, a proof for the Pythagorean theorem, proves that division by zero is infinity, computes π to 5 decimal places, and calculates the time taken for the Earth to orbit the Sun to 9 decimal places.

- 1130 – Al-Samawal al-Maghribi gave a definition of algebra: “[it is concerned] with operating on unknowns using all the arithmetical tools, in the same way as the arithmetician operates on the known.”[12]

- 1135 – Sharaf al-Din al-Tusi followed al-Khayyam’s application of algebra to geometry, and wrote a treatise on cubic equations that “represents an essential contribution to another algebra which aimed to study curves by means of equations, thus inaugurating the beginning of algebraic geometry”.[12]

- 1202 – Leonardo Fibonacci demonstrates the utility of Hindu–Arabic numerals in his Liber Abaci (Book of the Abacus).

- 1247 – Qin Jiushao publishes Shùshū Jiǔzhāng (Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections).

- 1248 – Li Ye writes Ceyuan haijing, a 12 volume mathematical treatise containing 170 formulas and 696 problems mostly solved by polynomial equations using the method tian yuan shu.

- 1260 – Al-Farisi gave a new proof of Thabit ibn Qurra’s theorem, introducing important new ideas concerning factorization and combinatorial methods. He also gave the pair of amicable numbers 17296 and 18416 that have also been jointly attributed to Fermat as well as Thabit ibn Qurra.[13]

- c. 1250 – Nasir al-Din al-Tusi attempts to develop a form of non-Euclidean geometry.

- 1280 – Guo Shoujing and Wang Xun use cubic interpolation for generating sine.

- 1303 – Zhu Shijie publishes Precious Mirror of the Four Elements, which contains an ancient method of arranging binomial coefficients in a triangle.

- 1356- Narayana Pandita completes his treatise Ganita Kaumudi, which for the first time contains Fermat’s factorization method, generalized fibonacci sequence, and the first ever algorithm to systematically generate all permutations as well as many new magic figure techniques.

- 14th century – Madhava discovers the power series expansion for sin�

, cos�

, arctan�

and �/4

[14][15] This theory is now well known in the Western world as the Taylor series or infinite series.[16]

- 14th century – Parameshvara Nambudiri, a Kerala school mathematician, presents a series form of the sine function that is equivalent to its Taylor series expansion, states the mean value theorem of differential calculus, and is also the first mathematician to give the radius of circle with inscribed cyclic quadrilateral.

15th century[edit]

- 1400 – Madhava discovers the series expansion for the inverse-tangent function, the infinite series for arctan and sin, and many methods for calculating the circumference of the circle, and uses them to compute π correct to 11 decimal places.

- c. 1400 – Jamshid al-Kashi “contributed to the development of decimal fractions not only for approximating algebraic numbers, but also for real numbers such as π. His contribution to decimal fractions is so major that for many years he was considered as their inventor. Although not the first to do so, al-Kashi gave an algorithm for calculating nth roots, which is a special case of the methods given many centuries later by [Paolo] Ruffini and [William George] Horner.” He is also the first to use the decimal point notation in arithmetic and Arabic numerals. His works include The Key of arithmetics, Discoveries in mathematics, The Decimal point, and The benefits of the zero. The contents of the Benefits of the Zero are an introduction followed by five essays: “On whole number arithmetic”, “On fractional arithmetic”, “On astrology”, “On areas”, and “On finding the unknowns [unknown variables]”. He also wrote the Thesis on the sine and the chord and Thesis on finding the first degree sine.

- 15th century – Ibn al-Banna’ al-Marrakushi and Abu’l-Hasan ibn Ali al-Qalasadi introduced symbolic notation for algebra and for mathematics in general.[12]

- 15th century – Nilakantha Somayaji, a Kerala school mathematician, writes the Aryabhatiya Bhasya, which contains work on infinite-series expansions, problems of algebra, and spherical geometry.

- 1424 – Ghiyath al-Kashi computes π to sixteen decimal places using inscribed and circumscribed polygons.

- 1427 – Jamshid al-Kashi completes The Key to Arithmetic containing work of great depth on decimal fractions. It applies arithmetical and algebraic methods to the solution of various problems, including several geometric ones.

- 1464 – Regiomontanus writes De Triangulis omnimodus which is one of the earliest texts to treat trigonometry as a separate branch of mathematics.

- 1478 – An anonymous author writes the Treviso Arithmetic.

- 1494 – Luca Pacioli writes Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalità; introduces primitive symbolic algebra using “co” (cosa) for the unknown.

Modern[edit]

16th century[edit]

- 1501 – Nilakantha Somayaji writes the Tantrasamgraha which is the first treatment of all 10 cases in spherical trigonometry.

- 1520 – Scipione del Ferro develops a method for solving “depressed” cubic equations (cubic equations without an x2 term), but does not publish.

- 1522 – Adam Ries explained the use of Arabic digits and their advantages over Roman numerals.

- 1535 – Nicolo Tartaglia independently develops a method for solving depressed cubic equations but also does not publish.

- 1539 – Gerolamo Cardano learns Tartaglia’s method for solving depressed cubics and discovers a method for depressing cubics, thereby creating a method for solving all cubics.

- 1540 – Lodovico Ferrari solves the quartic equation.

- 1544 – Michael Stifel publishes Arithmetica integra.

- 1545 – Gerolamo Cardano conceives the idea of complex numbers.

- 1550 – Jyeṣṭhadeva, a Kerala school mathematician, writes the Yuktibhāṣā which gives proofs of power series expansion of some trigonometry functions.

- 1572 – Rafael Bombelli writes Algebra treatise and uses imaginary numbers to solve cubic equations.

- 1584 – Zhu Zaiyu calculates equal temperament.

- 1596 – Ludolph van Ceulen computes π to twenty decimal places using inscribed and circumscribed polygons.

17th century[edit]

- 1614 – John Napier publishes a table of Napierian logarithms in Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio.

- 1617 – Henry Briggs discusses decimal logarithms in Logarithmorum Chilias Prima.

- 1618 – John Napier publishes the first references to e in a work on logarithms.

- 1619 – René Descartes discovers analytic geometry (Pierre de Fermat claimed that he also discovered it independently).

- 1619 – Johannes Kepler discovers two of the Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra.

- 1629 – Pierre de Fermat develops a rudimentary differential calculus.

- 1634 – Gilles de Roberval shows that the area under a cycloid is three times the area of its generating circle.

- 1636 – Muhammad Baqir Yazdi jointly discovered the pair of amicable numbers 9,363,584 and 9,437,056 along with Descartes (1636).[13]

- 1637 – Pierre de Fermat claims to have proven Fermat’s Last Theorem in his copy of Diophantus‘ Arithmetica.

- 1637 – First use of the term imaginary number by René Descartes; it was meant to be derogatory.

- 1643 – René Descartes develops Descartes’ theorem.

- 1654 – Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat create the theory of probability.

- 1655 – John Wallis writes Arithmetica Infinitorum.

- 1658 – Christopher Wren shows that the length of a cycloid is four times the diameter of its generating circle.

- 1665 – Isaac Newton works on the fundamental theorem of calculus and develops his version of infinitesimal calculus.

- 1668 – Nicholas Mercator and William Brouncker discover an infinite series for the logarithm while attempting to calculate the area under a hyperbolic segment.

- 1671 – James Gregory develops a series expansion for the inverse-tangent function (originally discovered by Madhava).

- 1671 – James Gregory discovers Taylor’s theorem.

- 1673 – Gottfried Leibniz also develops his version of infinitesimal calculus.

- 1675 – Isaac Newton invents an algorithm for the computation of functional roots.

- 1680s – Gottfried Leibniz works on symbolic logic.

- 1683 – Seki Takakazu discovers the resultant and determinant.

- 1683 – Seki Takakazu develops elimination theory.

- 1691 – Gottfried Leibniz discovers the technique of separation of variables for ordinary differential equations.

- 1693 – Edmund Halley prepares the first mortality tables statistically relating death rate to age.

- 1696 – Guillaume de l’Hôpital states his rule for the computation of certain limits.

- 1696 – Jakob Bernoulli and Johann Bernoulli solve brachistochrone problem, the first result in the calculus of variations.

- 1699 – Abraham Sharp calculates π to 72 digits but only 71 are correct.

18th century[edit]

- 1706 – John Machin develops a quickly converging inverse-tangent series for π and computes π to 100 decimal places.

- 1708 – Seki Takakazu discovers Bernoulli numbers. Jacob Bernoulli whom the numbers are named after is believed to have independently discovered the numbers shortly after Takakazu.

- 1712 – Brook Taylor develops Taylor series.

- 1722 – Abraham de Moivre states de Moivre’s formula connecting trigonometric functions and complex numbers.

- 1722 – Takebe Kenko introduces Richardson extrapolation.

- 1724 – Abraham De Moivre studies mortality statistics and the foundation of the theory of annuities in Annuities on Lives.

- 1730 – James Stirling publishes The Differential Method.

- 1733 – Giovanni Gerolamo Saccheri studies what geometry would be like if Euclid’s fifth postulate were false.

- 1733 – Abraham de Moivre introduces the normal distribution to approximate the binomial distribution in probability.

- 1734 – Leonhard Euler introduces the integrating factor technique for solving first-order ordinary differential equations.

- 1735 – Leonhard Euler solves the Basel problem, relating an infinite series to π.

- 1736 – Leonhard Euler solves the problem of the Seven bridges of Königsberg, in effect creating graph theory.

- 1739 – Leonhard Euler solves the general homogeneous linear ordinary differential equation with constant coefficients.

- 1742 – Christian Goldbach conjectures that every even number greater than two can be expressed as the sum of two primes, now known as Goldbach’s conjecture.

- 1747 – Jean le Rond d’Alembert solves the vibrating string problem (one-dimensional wave equation).[17]

- 1748 – Maria Gaetana Agnesi discusses analysis in Instituzioni Analitiche ad Uso della Gioventu Italiana.

- 1761 – Thomas Bayes proves Bayes’ theorem.

- 1761 – Johann Heinrich Lambert proves that π is irrational.

- 1762 – Joseph-Louis Lagrange discovers the divergence theorem.

- 1789 – Jurij Vega improves Machin’s formula and computes π to 140 decimal places, 136 of which were correct.

- 1794 – Jurij Vega publishes Thesaurus Logarithmorum Completus.

- 1796 – Carl Friedrich Gauss proves that the regular 17-gon can be constructed using only a compass and straightedge.

- 1796 – Adrien-Marie Legendre conjectures the prime number theorem.

- 1797 – Caspar Wessel associates vectors with complex numbers and studies complex number operations in geometrical terms.

- 1799 – Carl Friedrich Gauss proves the fundamental theorem of algebra (every polynomial equation has a solution among the complex numbers).

- 1799 – Paolo Ruffini partially proves the Abel–Ruffini theorem that quintic or higher equations cannot be solved by a general formula.

19th century[edit]

- 1801 – Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, Carl Friedrich Gauss’s number theory treatise, is published in Latin.

- 1805 – Adrien-Marie Legendre introduces the method of least squares for fitting a curve to a given set of observations.

- 1806 – Louis Poinsot discovers the two remaining Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra.

- 1806 – Jean-Robert Argand publishes proof of the Fundamental theorem of algebra and the Argand diagram.

- 1807 – Joseph Fourier announces his discoveries about the trigonometric decomposition of functions.

- 1811 – Carl Friedrich Gauss discusses the meaning of integrals with complex limits and briefly examines the dependence of such integrals on the chosen path of integration.

- 1815 – Siméon Denis Poisson carries out integrations along paths in the complex plane.

- 1817 – Bernard Bolzano presents the intermediate value theorem—a continuous function that is negative at one point and positive at another point must be zero for at least one point in between. Bolzano gives a first formal (ε, δ)-definition of limit.

- 1821 – Augustin-Louis Cauchy publishes Cours d’Analyse which purportedly contains an erroneous “proof” that the pointwise limit of continuous functions is continuous.

- 1822 – Augustin-Louis Cauchy presents the Cauchy’s integral theorem for integration around the boundary of a rectangle in the complex plane.

- 1822 – Irisawa Shintarō Hiroatsu analyzes Soddy’s hexlet in a Sangaku.

- 1823 – Sophie Germain’s Theorem is published in the second edition of Adrien-Marie Legendre’s Essai sur la théorie des nombres[18]

- 1824 – Niels Henrik Abel partially proves the Abel–Ruffini theorem that the general quintic or higher equations cannot be solved by a general formula involving only arithmetical operations and roots.

- 1825 – Augustin-Louis Cauchy presents the Cauchy integral theorem for general integration paths—he assumes the function being integrated has a continuous derivative, and he introduces the theory of residues in complex analysis.

- 1825 – Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet and Adrien-Marie Legendre prove Fermat’s Last Theorem for n = 5.

- 1825 – André-Marie Ampère discovers Stokes’ theorem.

- 1826 – Niels Henrik Abel gives counterexamples to Augustin-Louis Cauchy’s purported “proof” that the pointwise limit of continuous functions is continuous.

- 1828 – George Green proves Green’s theorem.

- 1829 – János Bolyai, Gauss, and Lobachevsky invent hyperbolic non-Euclidean geometry.

- 1831 – Mikhail Vasilievich Ostrogradsky rediscovers and gives the first proof of the divergence theorem earlier described by Lagrange, Gauss and Green.

- 1832 – Évariste Galois presents a general condition for the solvability of algebraic equations, thereby essentially founding group theory and Galois theory.

- 1832 – Lejeune Dirichlet proves Fermat’s Last Theorem for n = 14.

- 1835 – Lejeune Dirichlet proves Dirichlet’s theorem about prime numbers in arithmetical progressions.

- 1837 – Pierre Wantzel proves that doubling the cube and trisecting the angle are impossible with only a compass and straightedge, as well as the full completion of the problem of constructability of regular polygons.

- 1837 – Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet develops Analytic number theory.

- 1838 – First mention of uniform convergence in a paper by Christoph Gudermann; later formalized by Karl Weierstrass. Uniform convergence is required to fix Augustin-Louis Cauchy erroneous “proof” that the pointwise limit of continuous functions is continuous from Cauchy’s 1821 Cours d’Analyse.

- 1841 – Karl Weierstrass discovers but does not publish the Laurent expansion theorem.

- 1843 – Pierre-Alphonse Laurent discovers and presents the Laurent expansion theorem.

- 1843 – William Hamilton discovers the calculus of quaternions and deduces that they are non-commutative.

- 1844 – Hermann Grassmann publishes his Ausdehnungslehre, from which linear algebra is later developed.

- 1847 – George Boole formalizes symbolic logic in The Mathematical Analysis of Logic, defining what is now called Boolean algebra.

- 1849 – George Gabriel Stokes shows that solitary waves can arise from a combination of periodic waves.

- 1850 – Victor Alexandre Puiseux distinguishes between poles and branch points and introduces the concept of essential singular points.

- 1850 – George Gabriel Stokes rediscovers and proves Stokes’ theorem.

- 1854 – Bernhard Riemann introduces Riemannian geometry.

- 1854 – Arthur Cayley shows that quaternions can be used to represent rotations in four-dimensional space.

- 1858 – August Ferdinand Möbius invents the Möbius strip.

- 1858 – Charles Hermite solves the general quintic equation by means of elliptic and modular functions.

- 1859 – Bernhard Riemann formulates the Riemann hypothesis, which has strong implications about the distribution of prime numbers.

- 1868 – Eugenio Beltrami demonstrates independence of Euclid’s parallel postulate from the other axioms of Euclidean geometry.

- 1870 – Felix Klein constructs an analytic geometry for Lobachevski’s geometry thereby establishing its self-consistency and the logical independence of Euclid’s fifth postulate.

- 1872 – Richard Dedekind invents what is now called the Dedekind Cut for defining irrational numbers, and now used for defining surreal numbers.

- 1873 – Charles Hermite proves that e is transcendental.

- 1873 – Georg Frobenius presents his method for finding series solutions to linear differential equations with regular singular points.

- 1874 – Georg Cantor proves that the set of all real numbers is uncountably infinite but the set of all real algebraic numbers is countably infinite. His proof does not use his diagonal argument, which he published in 1891.

- 1882 – Ferdinand von Lindemann proves that π is transcendental and that therefore the circle cannot be squared with a compass and straightedge.

- 1882 – Felix Klein invents the Klein bottle.

- 1895 – Diederik Korteweg and Gustav de Vries derive the Korteweg–de Vries equation to describe the development of long solitary water waves in a canal of rectangular cross section.

- 1895 – Georg Cantor publishes a book about set theory containing the arithmetic of infinite cardinal numbers and the continuum hypothesis.

- 1895 – Henri Poincaré publishes paper “Analysis Situs” which started modern topology.

- 1896 – Jacques Hadamard and Charles Jean de la Vallée-Poussin independently prove the prime number theorem.

- 1896 – Hermann Minkowski presents Geometry of numbers.

- 1899 – Georg Cantor discovers a contradiction in his set theory.

- 1899 – David Hilbert presents a set of self-consistent geometric axioms in Foundations of Geometry.

- 1900 – David Hilbert states his list of 23 problems, which show where some further mathematical work is needed.

Contemporary[edit]

20th century[edit]

- 1901 – Élie Cartan develops the exterior derivative.

- 1901 – Henri Lebesgue publishes on Lebesgue integration.

- 1903 – Carle David Tolmé Runge presents a fast Fourier transform algorithm[citation needed]

- 1903 – Edmund Georg Hermann Landau gives considerably simpler proof of the prime number theorem.

- 1908 – Ernst Zermelo axiomizes set theory, thus avoiding Cantor’s contradictions.

- 1908 – Josip Plemelj solves the Riemann problem about the existence of a differential equation with a given monodromic group and uses Sokhotsky – Plemelj formulae.

- 1912 – Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer presents the Brouwer fixed-point theorem.

- 1912 – Josip Plemelj publishes simplified proof for the Fermat’s Last Theorem for exponent n = 5.

- 1915 – Emmy Noether proves her symmetry theorem, which shows that every symmetry in physics has a corresponding conservation law.

- 1916 – Srinivasa Ramanujan introduces Ramanujan conjecture. This conjecture is later generalized by Hans Petersson.

- 1919 – Viggo Brun defines Brun’s constant B2 for twin primes.

- 1921 – Emmy Noether introduces the first general definition of a commutative ring.

- 1928 – John von Neumann begins devising the principles of game theory and proves the minimax theorem.

- 1929 – Emmy Noether introduces the first general representation theory of groups and algebras.

- 1930 – Casimir Kuratowski shows that the three-cottage problem has no solution.

- 1931 – Kurt Gödel proves his incompleteness theorem, which shows that every axiomatic system for mathematics is either incomplete or inconsistent.

- 1931 – Georges de Rham develops theorems in cohomology and characteristic classes.

- 1933 – Karol Borsuk and Stanislaw Ulam present the Borsuk–Ulam antipodal-point theorem.

- 1933 – Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov publishes his book Basic notions of the calculus of probability (Grundbegriffe der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung), which contains an axiomatization of probability based on measure theory.

- 1936 – Alonzo Church and Alan Turing create, respectively, the λ-calculus and the Turing machine, formalizing the notion of computation and computability.

- 1938 – Tadeusz Banachiewicz introduces LU decomposition.

- 1940 – Kurt Gödel shows that neither the continuum hypothesis nor the axiom of choice can be disproven from the standard axioms of set theory.

- 1942 – G.C. Danielson and Cornelius Lanczos develop a fast Fourier transform algorithm.

- 1943 – Kenneth Levenberg proposes a method for nonlinear least squares fitting.

- 1945 – Stephen Cole Kleene introduces realizability.

- 1945 – Saunders Mac Lane and Samuel Eilenberg start category theory.

- 1945 – Norman Steenrod and Samuel Eilenberg give the Eilenberg–Steenrod axioms for (co-)homology.

- 1946 – Jean Leray introduces the Spectral sequence.

- 1947 – George Dantzig publishes the simplex method for linear programming.

- 1948 – John von Neumann mathematically studies self-reproducing machines.

- 1948 – Atle Selberg and Paul Erdős prove independently in an elementary way the prime number theorem.

- 1949 – John Wrench and L.R. Smith compute π to 2,037 decimal places using ENIAC.

- 1949 – Claude Shannon develops notion of Information Theory.

- 1950 – Stanisław Ulam and John von Neumann present cellular automata dynamical systems.

- 1953 – Nicholas Metropolis introduces the idea of thermodynamic simulated annealing algorithms.

- 1955 – H. S. M. Coxeter et al. publish the complete list of uniform polyhedron.

- 1955 – Enrico Fermi, John Pasta, Stanisław Ulam, and Mary Tsingou numerically study a nonlinear spring model of heat conduction and discover solitary wave type behavior.

- 1956 – Noam Chomsky describes a hierarchy of formal languages.

- 1956 – John Milnor discovers the existence of an Exotic sphere in seven dimensions, inaugurating the field of differential topology.

- 1957 – Kiyosi Itô develops Itô calculus.

- 1957 – Stephen Smale provides the existence proof for crease-free sphere eversion.

- 1958 – Alexander Grothendieck‘s proof of the Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem is published.

- 1959 – Kenkichi Iwasawa creates Iwasawa theory.

- 1960 – Tony Hoare invents the quicksort algorithm.

- 1960 – Irving S. Reed and Gustave Solomon present the Reed–Solomon error-correcting code.

- 1961 – Daniel Shanks and John Wrench compute π to 100,000 decimal places using an inverse-tangent identity and an IBM-7090 computer.

- 1961 – John G. F. Francis and Vera Kublanovskaya independently develop the QR algorithm to calculate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a matrix.

- 1961 – Stephen Smale proves the Poincaré conjecture for all dimensions greater than or equal to 5.

- 1962 – Donald Marquardt proposes the Levenberg–Marquardt nonlinear least squares fitting algorithm.

- 1963 – Paul Cohen uses his technique of forcing to show that neither the continuum hypothesis nor the axiom of choice can be proven from the standard axioms of set theory.

- 1963 – Martin Kruskal and Norman Zabusky analytically study the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou heat conduction problem in the continuum limit and find that the KdV equation governs this system.

- 1963 – meteorologist and mathematician Edward Norton Lorenz published solutions for a simplified mathematical model of atmospheric turbulence – generally known as chaotic behaviour and strange attractors or Lorenz Attractor – also the Butterfly Effect.

- 1965 – Iranian mathematician Lotfi Asker Zadeh founded fuzzy set theory as an extension of the classical notion of set and he founded the field of Fuzzy mathematics.

- 1965 – Martin Kruskal and Norman Zabusky numerically study colliding solitary waves in plasmas and find that they do not disperse after collisions.

- 1965 – James Cooley and John Tukey present an influential fast Fourier transform algorithm.

- 1966 – E. J. Putzer presents two methods for computing the exponential of a matrix in terms of a polynomial in that matrix.

- 1966 – Abraham Robinson presents non-standard analysis.

- 1967 – Robert Langlands formulates the influential Langlands program of conjectures relating number theory and representation theory.

- 1968 – Michael Atiyah and Isadore Singer prove the Atiyah–Singer index theorem about the index of elliptic operators.

- 1973 – Lotfi Zadeh founded the field of fuzzy logic.

- 1974 – Pierre Deligne solves the last and deepest of the Weil conjectures, completing the program of Grothendieck.

- 1975 – Benoit Mandelbrot publishes Les objets fractals, forme, hasard et dimension.

- 1976 – Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken use a computer to prove the Four color theorem.

- 1981 – Richard Feynman gives an influential talk “Simulating Physics with Computers” (in 1980 Yuri Manin proposed the same idea about quantum computations in “Computable and Uncomputable” (in Russian)).

- 1983 – Gerd Faltings proves the Mordell conjecture and thereby shows that there are only finitely many whole number solutions for each exponent of Fermat’s Last Theorem.

- 1984 – Vaughan Jones discovers the Jones polynomial in knot theory, which leads to other new knot polynomials as well as connections between knot theory and other fields.

- 1985 – Louis de Branges de Bourcia proves the Bieberbach conjecture.

- 1986 – Ken Ribet proves Ribet’s theorem.

- 1987 – Yasumasa Kanada, David Bailey, Jonathan Borwein, and Peter Borwein use iterative modular equation approximations to elliptic integrals and a NEC SX-2 supercomputer to compute π to 134 million decimal places.

- 1991 – Alain Connes and John W. Lott develop non-commutative geometry.

- 1992 – David Deutsch and Richard Jozsa develop the Deutsch–Jozsa algorithm, one of the first examples of a quantum algorithm that is exponentially faster than any possible deterministic classical algorithm.

- 1994 – Andrew Wiles proves part of the Taniyama–Shimura conjecture and thereby proves Fermat’s Last Theorem.

- 1994 – Peter Shor formulates Shor’s algorithm, a quantum algorithm for integer factorization.

- 1995 – Simon Plouffe discovers Bailey–Borwein–Plouffe formula capable of finding the nth binary digit of π.

- 1998 – Thomas Callister Hales (almost certainly) proves the Kepler conjecture.

- 1999 – the full Taniyama–Shimura conjecture is proven.

- 2000 – the Clay Mathematics Institute proposes the seven Millennium Prize Problems of unsolved important classic mathematical questions.

21st century[edit]

- 2002 – Manindra Agrawal, Nitin Saxena, and Neeraj Kayal of IIT Kanpur present an unconditional deterministic polynomial time algorithm to determine whether a given number is prime (the AKS primality test).

- 2002 – Preda Mihăilescu proves Catalan’s conjecture.

- 2003 – Grigori Perelman proves the Poincaré conjecture.

- 2004 – the classification of finite simple groups, a collaborative work involving some hundred mathematicians and spanning fifty years, is completed.

- 2004 – Ben Green and Terence Tao prove the Green–Tao theorem.

- 2009 – Fundamental lemma (Langlands program) is proved by Ngô Bảo Châu.[20]

- 2010 – Larry Guth and Nets Hawk Katz solve the Erdős distinct distances problem.

- 2013 – Yitang Zhang proves the first finite bound on gaps between prime numbers.[21]

- 2014 – Project Flyspeck[22] announces that it completed a proof of Kepler’s conjecture.[23][24][25][26]

- 2015 – Terence Tao solves The Erdős discrepancy problem .

- 2015 – László Babai finds that a quasipolynomial complexity algorithm would solve the Graph isomorphism problem.

- 2016 – Maryna Viazovska solves the sphere packing problem in dimension 8. Subsequent work building on this leads to a solution for dimension 24

Timeline of ancient Greek mathematicians

3 languages

Tools

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

See also: List of Greek mathematicians and Chronology of ancient Greek mathematicians

This is a timeline of mathematicians in ancient Greece.

| Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Greece |

| showNeolithic Greece |

| showGreek Bronze Age |

| showAncient Greece |

| showMedieval Greece |

| showEarly modern Greece |

| showModern Greece |

| showHistory by topic |

| vte |

Timeline[edit]

Historians traditionally place the beginning of Greek mathematics proper to the age of Thales of Miletus (ca. 624–548 BC), which is indicated by the green line at 600 BC. The orange line at 300 BC indicates the approximate year in which Euclid‘s Elements was first published. The red line at 300 AD passes through Pappus of Alexandria (c. 290 – c. 350 AD), who was one of the last great Greek mathematicians of late antiquity. Note that the solid thick black line is at year zero, which is a year that does not exist in the Anno Domini (AD) calendar year system

|

The mathematician Heliodorus of Larissa is not listed due to the uncertainty of when he lived, which was possibly during the 3rd century AD, after Ptolemy.

Overview of the most important mathematicians and discoveries[edit]

Of these mathematicians, those whose work stands out include:

- Thales of Miletus (c. 624/623 – c. 548/545 BC) is the first known individual to use deductive reasoning applied to geometry, by deriving four corollaries to Thales’ theorem. He is the first known individual to whom a mathematical discovery has been attributed.[1]

- Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BC) was credited with many mathematical and scientific discoveries, including the Pythagorean theorem, Pythagorean tuning, the five regular solids, the Theory of Proportions, the sphericity of the Earth, and the identity of the morning and evening stars as the planet Venus.

- Theaetetus (c. 417 – c. 369 BC) Proved that there are exactly five regular convex polyhedra (it is emphasized that it was, in particular, proved that there does not exist any regular convex polyhedra other than these five). This fact led these five solids, now called the Platonic solids, to play a prominent role in the philosophy of Plato (and consequently, also influenced later Western Philosophy) who associated each of the four classical elements with a regular solid: earth with the cube, air with the octahedron, water with the icosahedron, and fire with the tetrahedron (of the fifth Platonic solid, the dodecahedron, Plato obscurely remarked, “…the god used [it] for arranging the constellations on the whole heaven”). The last book (Book XIII) of the Euclid’s Elements, which is probably derived from the work of Theaetetus, is devoted to constructing the Platonic solids and describing their properties; Andreas Speiser has advocated the view that the construction of the 5 regular solids is the chief goal of the deductive system canonized in the Elements.[2] Astronomer Johannes Kepler proposed a model of the Solar System in which the five solids were set inside one another and separated by a series of inscribed and circumscribed spheres.

- Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 408 – c. 355 BC) is considered by some to be the greatest of classical Greek mathematicians, and in all antiquity second only to Archimedes.[3] Book V of Euclid’s Elements is though to be largely due to Eudoxus.

- Aristarchus of Samos (c. 310 – c. 230 BC) presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the known universe with the Earth revolving around it. Aristarchus identified the “central fire” with the Sun, and he put the other planets in their correct order of distance around the Sun.[4] In On the Sizes and Distances, he calculates the sizes of the Sun and Moon, as well as their distances from the Earth in terms of Earth’s radius. However, Eratosthenes (c. 276 – c. 194/195 BC) was the first person to calculate the circumference of the Earth. Posidonius (c. 135 – c. 51 BC) also measured the diameters and distances of the Sun and the Moon as well as the Earth’s diameter; his measurement of the diameter of the Sun was more accurate than Aristarchus’, differing from the modern value by about half.

- Euclid (fl. 300 BC) is often referred to as the “founder of geometry“[5] or the “father of geometry” because of his incredibly influential treatise called the Elements, which was the first, or at least one of the first, axiomatized deductive systems.

- Archimedes (c. 287 – c. 212 BC) is considered to be the greatest mathematician of ancient history, and one of the greatest of all time.[6][7] Archimedes anticipated modern calculus and analysis by applying concepts of infinitesimals and the method of exhaustion to derive and rigorously prove a range of geometrical theorems, including: the area of a circle; the surface area and volume of a sphere; area of an ellipse; the area under a parabola; the volume of a segment of a paraboloid of revolution; the volume of a segment of a hyperboloid of revolution; and the area of a spiral.[8] He was also one of the first to apply mathematics to physical phenomena, founding hydrostatics and statics, including an explanation of the principle of the lever. In a lost work, he discovered and enumerated the 13 Archimedean solids, which were later rediscovered by Johannes Kepler around 1620 A.D.

- Apollonius of Perga (c. 240 – c. 190 BC) is known for his work on conic sections and his study of geometry in 3-dimensional space. He is considered one of the greatest ancient Greek mathematicians.

- Hipparchus (c. 190 – c. 120 BC) is considered the founder of trigonometry[9] and also solved several problems of spherical trigonometry. He was the first whose quantitative and accurate models for the motion of the Sun and Moon survive. In his work On Sizes and Distances, he measured the apparent diameters of the Sun and Moon and their distances from Earth. He is also reputed to have measured the Earth’s precession.

- Diophantus (c. 201–215 – c. 285–299 AD) wrote Arithmetica which dealt with solving algebraic equations and also introduced syncopated algebra, which was a precursor to modern symbolic algebra. Because of this, Diophantus is sometimes known as “the father of algebra,” which is a title he shares with Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi. In contrast to Diophantus, al-Khwarizmi wasn’t primarily interested in integers and he gave an exhaustive and systematic description of solving quadratic equations and some higher order algebraic equations. However, al-Khwarizmi did not use symbolic or syncopated algebra but rather “rhetorical algebra” or ancient Greek “geometric algebra” (the ancient Greeks had expressed and solved some particular instances of algebraic equations in terms of geometric properties such as length and area but they did not solve such problems in general; only particular instances). An example of “geometric algebra” is: given a triangle (or rectangle, etc.) with a certain area and also given the length of some of its sides (or some other properties), find the length of the remaining side (and justify/prove the answer with geometry). Solving such a problem is often equivalent to finding the roots of a polynomial.

Hellenic mathematicians[edit]

The conquests of Alexander the Great around c. 330 BC led to Greek culture being spread around much of the Mediterranean region, especially in Alexandria, Egypt. This is why the Hellenistic period of Greek mathematics is typically considered as beginning in the 4th century BC. During the Hellenistic period, many people living in those parts of the Mediterranean region subject to Greek influence ended up adopting the Greek language and sometimes also Greek culture. Consequently, some of the Greek mathematicians from this period may not have been “ethnically Greek” with respect to the modern Western notion of ethnicity, which is much more rigid than most other notions of ethnicity that existed in the Mediterranean region at the time. Ptolemy, for example, was said to have originated from Upper Egypt, which is far South of Alexandria, Egypt. Regardless, their contemporaries considered them Greek.

Straightedge and compass constructions[edit]

Main article: Straightedge and compass construction

For the most part, straightedge and compass constructions dominated ancient Greek mathematics and most theorems and results were stated and proved in terms of geometry. These proofs involved a straightedge (such as that formed by a taut rope), which was used to construct lines, and a compass, which was used to construct circles. The straightedge is an idealized ruler that can draw arbitrarily long lines but (unlike modern rulers) it has no markings on it. A compass can draw a circle starting from two given points: the center and a point on the circle. A taut rope can be used to physically construct both lines (since it forms a straightedge) and circles (by rotating the taut rope around a point).

Geometric constructions using lines and circles were also used outside of the Mediterranean region. The Shulba Sutras from the Vedic period of Indian mathematics, for instance, contains geometric instructions on how to physically construct a (quality) fire-altar by using a taut rope as a straightedge. These alters could have various shapes but for theological reasons, they were all required to have the same area. This consequently required a high precision construction along with (written) instructions on how to geometrically construct such alters with the tools that were most widely available throughout the Indian subcontinent (and elsewhere) at the time. Ancient Greek mathematicians went one step further by axiomatizing plane geometry in such a way that straightedge and compass constructions became mathematical proofs. Euclid‘s Elements was the culmination of this effort and for over two thousand years, even as late as the 19th century, it remained the “standard text” on mathematics throughout the Mediterranean region (including Europe and the Middle East), and later also in North and South America after European colonization.

Algebra[edit]

Ancient Greek mathematicians are known to have solved specific instances of polynomial equations with the use of straightedge and compass constructions, which simultaneously gave a geometric proof of the solution’s correctness. Once a construction was completed, the answer could be found by measuring the length of a certain line segment (or possibly some other quantity). A quantity multiplied by itself, such as 5⋅5

You must be logged in to post a comment.